Context

African swine fever (or ASF), is a highly contagious viral disease which affects domestic and wild pigs. The disease has become a global threat to the entire pig industry and beyond. Once infected, pigs with ASFV suffer from internal hemorrhaging and will ultimately die within 10 days.

There is no available vaccine or treatment for the disease yet, which means it is spreading across the globe and disrupting basic protein availability, consumption patterns and the international meat trade. However, the disease also presents a blockbuster opportunity for those involved in understanding the science of the disease and in developing interventions to combat its spread.

So, what do we actually know about this disease?

Ingentium in collaboration with IHSMarkit Agribusiness Intelligence carried out a comprehensive review of ASF and its global impact. The full report, published as Animal Pharm: African Swine Fever 2020, can be found on the IHSMarkit Agribusiness Intelligence website. This blog provides some key takeaway points from the Report for our readers’/viewers’ consideration.

Disease Overview

ASF is endemic in many African countries, to which it was limited until 2007 when the ASFV entered the country of Georgia. It has since gone on to rapidly spread across Europe and Asia, reaching China in August 2018.

As of the end of 2019, presence of ASF has been confirmed in Romania in domestic pig populations, and throughout much of east and central Europe within wild boar populations. In Asia, AFS has spread from Russia to China followed by Cambodia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, South Korea, North Korea, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar, Philippines, Timor Leste and Vietnam.

The African swine fever virus (ASFV) affects all members of the pig family, including domesticated swine, European wild boars, warthogs, bush pigs and the giant forest hogs. ASF does not currently pose a risk to human health as it cannot be transmitted to human beings.

The ASFV can be transmitted directly, indirectly through contaminated feed and fomites, or can be vector-borne and transmitted through ticks. Once the ASFV has been introduced, infected swine develop high viral loads which are easily shed and lead to further direct or indirect transmission via fomites, on items like contaminated clothing, shoes, equipment and vehicles. Infection through contamination (whether feed or, for example, mud on a transport vehicle) is considered to be of primary concern. This is why many European countries focused on raising awareness on biosecurity. This is also why there has been a drive to develop feed additives that can inactivate ASFV within feed.

Wild boar has also played an important role in spreading the disease; however, larger geographical leaps in the spread of the disease have been the result of human activity and the international transportation of domestic pigs. For example, the first outbreak of ASF outside Africa, was recorded in 1957 in Portugal, where it is presumed to have been caused by the feeding of pigs near Lisbon airport with food waste containing pork from Angola.

As mentioned previously, there is no vaccine against ASF (although in China – false products claiming to be ASF vaccines have been marketed to farmers!)

Implementation of ASF control methods varies among countries depending on the epidemiological status of the disease, that is whether its endemic or not, and the predominant type of pig production, traditional or backyard vs commercial.

Some of the most important biosecurity measures to prevent the entrance of ASF into a commercial farm include:

- Fences,

- Restriction of visitors and vehicles,

- Use of dedicated clothes and footwear,

- Safe disposal of carcasses,

- Avoiding the use of potential contaminated feed including swill, and

- Introduction of new animals via quarantine and from well-known sources.

In fact, the Czech Republic demonstrated in 2017, after ASF was detected in 2 wild boar, how proper biosecurity measures can eliminate ASF. The country took various measures including increased passive surveillance, ban on hunting and wild boar feeding and enclosing the risk-area with “odour” and electric fences to ensure that the disease would remain contained and not spread any further throughout the country or the region. The last confirmed case of ASF in the Czech Republic was in February 2018.

Disease Impact

Broadly speaking, the presence of ASF has led to a dramatic decrease in pig populations leading to shortened supplies of pork, breeding stock, and in some cases significant price increases. This is most notable in China where the price of pork has increased significantly, and where the share prices of breeding companies also increased due to high demand for pork.

China, the USA, Germany, Spain and Brazil are the world’s top pig producers, producing over 60% of the world’s pigs. Pig production in these countries is made up of specialised medium-to-large intensive commercial farms – except for China which we will move onto shortly.

In contrast, there are traditional or backyard operations which are more susceptible to ASF due to low implementation of adequate biosecurity measures and the use of swill feed which remains an important mode of transmission of the disease. It is worth noting, that countries in which ASF is endemic are primarily reliant on backyard operations.

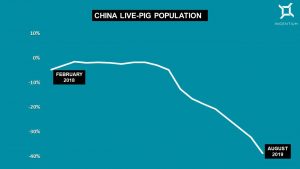

China has lost an estimated 50% of its pig population since the first reported case of ASF in 2018. Unlike the other top producing nations, China has a large share of backyard operations. It is reported that 85% of the herd population loss has occurred among small scale and backyard producers.

The losses have led to unprecedented shortages in the country’s pork supply, which has altered global trade flows and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. In order to cater for the increasing demand in the wake of production loss, global exports of pork are predicted to increase by 10 % (at 10.4 million tons) in 2020- a record high. Nonetheless, it is believed that even through the increase of imports, China will struggle to make up for its reduced production capacity due to ASF.

Review of the State of the Art

Vaccination is, in principle, the most effective way of controlling animal viral diseases through preventing mortality or reducing morbidity. Live attenuated vaccines for ASF were used in the 1960s in Spain and Portugal, but they led to the appearance of chronic forms of ASF.

All other approaches including inactivated viruses, recombinant proteins and DNA vaccines, have not yielded as yet, an effective and safe ASF vaccine.

As a result of this, we have seen a global increase in the number of ASF-related technologies being patented in the last 10 years. Based on this trend, it is expected that patent filings and R&D funding will continue to grow over the next few years.

A mixture of both public and private-sector organisations appears as applicants (the owners) on ASF-related patents. Some notable applicants include the University of Yangzhou in China, which has been carrying out research on ASF as early as the mid-2000s, and filed its latest ASF related patent in 2019.

In the USA, the US Department of Agriculture has patent filings which claim ASF vaccine technologies with a focus on the ASFV Georgia 2007 isolate and finally in Europe, Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica (DE) appears as a top applicant. Some of these organisations have (or are in the process) commercialising their vaccine technologies. There are also other forms of interventions being developed, including genetically modified pigs which are resistant to ASF. Buyers of this report also gain access to a detailed list of patents and patent applications related to ASF globally.

Final Thoughts

The European Commission estimates a timeline of around 8 years with a probability of success varying between 50 and 80%. In the short-term, the live attenuated vaccines (LAVs) are the most promising candidates, but further research is needed to confirm their safety and efficacy in long-term controlled experiments.

Given the spread of ASF across various farming systems and geographies, it is important to consider what a target product profile should look like for an ASF vaccine. Our report suggests what a minimal and ideal target product profile would look like for an ASF vaccine.

Our report also provides further insight on the impact of ASF on international trade and ancillary industries (such as feed) as well as socio-economics. Lastly, we have estimated the potential value of an ASF vaccine for the Asian market where ASF is currently ravaging domestic production.

Further Reading

|

This comprehensive African Swine Fever 2020 report is available for purchase through IHSMarkit Agribusiness Intelligence. Visit their website to view the full table of contents, and also read excerpts, from this report. You can also reach out to IHSMarkit with regards to this report by emailing: agrimarketing@ihsmarkit.com |

We hope that this short(ish) vlog/blog sparked your interest in ASF. As always, please feel free to get in touch with us. Also, if you liked this blog or the accompanying vlog – you can subscribe to our quarterly newsletter to stay IN THE KNOW w/ Ingentium.